Postscript (correction: ‘prescript‘) added July 2019:

You have arrived at a 2014 posting. That was the year in which this investigator finally abandoned the notion of the body image being made by direct scorch off a heated metal template (despite many attractions, like negative image, 3D response etc. But hear later: orchestral DA DA! Yup, still there with the revised technology! DA DA! ).

In its place came two stage image production.

.

Stage 1: sprinkle white wheaten flour or suchlike vertically onto human subject from head to foot, front and rear (ideally with initial smear of oil to act as weak adhesive). Shake off excess flour, then cover the lightly coated subject with wet linen. Press down VERTICALLY and firmly (thus avoiding sides of subject). Then (and here’s the key step):

Stage 2: suspend the linen horizontally over glowing charcoal embers and roast gently until the desired degree of coloration, thus ‘developing’ the flour imprint, so as to simulate a sweat-generated body image that has become yellowed with centuries of ageing.

.

The novel two-stage “flour-imprinting’ technology was unveiled initially on my generalist “sciencebuzz” site. (Warning: one has to search assiduously to find it, and it still uses a metal template, albeit unheated, as distinct from human anatomy):

So it’s still thermal development of sorts, but with a key difference. One can take imprints off human anatomy (dead or alive!).

A final wash of the roasted flour imprint with soap and water yields a straw-coloured nebulous image, i.e. with fuzzy, poorly defined edges. It’s still a negative (tone-reversed) image that responds to 3D-rendering software, notably the splendid freely-downloadable ImageJ. (Ring any bells? Better still, orchestral accompaniment – see , correction HEAR earlier – DA DA!))

.

This 2014 “prescript” replaces the one used for my earlier 2012/2013 postings, deploying abandoned ‘direct scorch’ technology.

Thank you for your patience and forbearance. Here’s where the original posting started:

Original posting starts here:

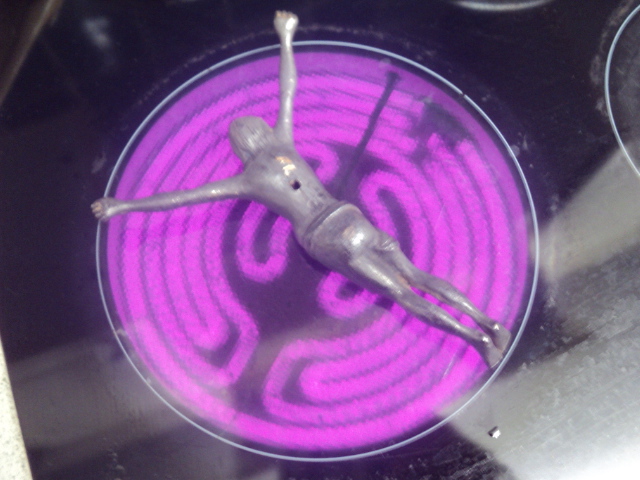

Modelling the Shroud image: from heated brass crucifix (left) to 3D-enhanced light/dark reversed scorch image (right). Not 100% there yet, but arguably making progress.

The first recorded appearance of the TS was in the tiny French hamlet of Lirey, south of Troyes in 1357. Why then, one may ask, at that particular era of French history, given there’s no evidence of where it had come from? And why was the image so peculiar, quite unlike anything that preceded it (allegedly) or anything that followed (allegedly). Apologies for the expressions of doubt in parentheses. All will be explained shortly.

This science-oriented blogger now believes, after some 3 years of scientific and historical detective work, that there is a simple answer to both those questions. What’s more, there WAS a precedent for the TS image in the 14th century, at least conceptually, and there are modern day experimental models too, at least approximately. See my photograph above (taken just an hour ago).

Perhaps the easiest way to understand the TS is to go back seven years from 1357 to 1350. That was declared a “Holy Year” in the calendar of the Roman Church in Europe. What’s more, there was an existing ‘holy relic’ that had captured public imagination, one that has been described as the Church’s “central icon”. It was so valued, so revered that “wherever the Church went, the relic went with it” (according to Neil MacGregor , celebrated art historian and currently Director of the British Museum). As an old boss of mine was wont to say: “No mean slouch”.

Here’s a slightly edited passage from a book I’ve just discovered from googling. It’s entitled “The Templars and the Grail, Knights of the Quest” (by one Karen Ralls). The editing is designed to keep you in suspense , dear reader.

“Preserved in Rome as a matter of record since at least 1011 and venerated by pilgrims, the icon in question was seen publicly very rarely, but one of those rare occasions was in that Holy Year 1350- when it was displayed to a rapturous audience of pilgrims. It was the talk of Europe. Papal records show that in the jubilee years 1300 and 1350, many people were trampled in the rush to look upon the icon which was said to cure all ills, including leprosy.”

So what was this icon that has such enormous pulling power, and why?

OK, time to come clean: It was the fabled “Veil of Veronica”, a central feature of all that follows.

Of all the representations of the Veil of Veronica on internet image files, this is perhaps the one that looks least like a painting, and one where the artist has at least paid lip service to the idea that it was an image created with bodily sweat. But it’s still a positive image note, from looking at the distribution of light and shade, so is not only diff erent from the TS, but xi be said to fail the diagnostic test for an imprint. It’s still a painting, albeit monochrome – the artist’s only concession to alleged imprinting mechanism.

Here’s how the same Karen Ralls introduced the above section:

The well-known story of the lady Veronica tells how she compassionately wiped the face of Christ as he was carrying the cross through the streets of Jerusalem, on the way to his Crucifixion. It is said that as a reward for her kindness, an image of his face miraculously remained on the cloth. So powerful was the medieval cult that grew around scene, that the incident became the sixth of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. Yet ironically the story appears nowhere in the Gospels. The cloth, preserved as a relic, became known as the Veil of Veronica. Some historians have identified it with the Mandylion of Edessa, which disappeared in 1204 after the siege of Constantinople.

Present whereabouts of the Veil of Veronica? No one knows for certain whether the one that caused all the stir in 1350 still exists or not. The problem is the existence of many icons that claim to be it. But many look less like a sweat imprint on fabric, as originally described, even with some miraculous enhancement (we are told) . Instead they look more like artistic representations with common pigments (art historian Charles Freeman would love ‘em 😉

From wiki:

There are at least six images in existence which bear a marked resemblance to each other and which are claimed to be the original Veil, a direct copy of it or, in two cases, the Mandylion. Each member of this group is enclosed in an elaborate outer frame with a gilded metal sheet (or riza in Russian) within, in which is cut an aperture where the face appears; at the lower extreme of the face there are three points which correspond to the shape of the hair and beard.

However, what matters for the purpose of this communication is not whether the Veronica that was on display in 1350 was genuine or not, or whether it was simply a sweat imprint, or an enhanced version of sweat, whether as a result of human art or divine intervention. It’s the medieval perception of the Veil as having ORIGINALLY been a sweat imprint of the face of Jesus onto some fabric proferred by a sympathetic bystander, while carrying his cross.

There must have been at least some who, viewing, or even hearing of the Veil, must have asked themselves: how can plain old perspiration (“sweat” in common parlance) imprint an image on cloth? What would it look like initially? What would it look like a day later, a week later, a century or millennium later? And among those people, might there be just one individual who then asked themselves an audacious question: could or might the process be simulated, or to put it baldly, faked? Could one pass off an entirely and audaciously man-made image as that of a divine sweat image? And if that were the case, what would be the most profitable way of doing that? Content oneself with producing a face imprint that was superior to that on the Veil, and claim that one had the “real” version, and that the one in Rome was the fake? Or avoid any such controversy and unpleasantness. Instead, marshall one’s technology to make an even more audacious claim, namely that one had not only an image that captured the face of Jesus, but that of his entire body! How could that be done? Was there a scenario from the New Testament gospels that might be adduced to back one’s claim?

Certainly there was, and it’s one that occurred just a day or two AFTER the crucifixion. It was the initial placement by Joseph of Arimathea of Jesus on a costly sheet of linen, conveniently with no reference at this stage to the body being cleaned of blood and other bodily secretions, notably sweat.

Already a plan for developing that germ of an idea was taking shape. What were the criteria that could be adopted first to produce a whole body imprint of the crucified Jesus that would pass muster, yet importantly pose no threat to the status of the Veil?

Here are a few:

1. The image must NOT be mistaken for anything but a burial shroud. A single image of the frontal side might be mistaken for some kind of painted portrait. Solution: imprint BOTH sides of the body, align them head to head making it seems as though a body had been first been laid on the lower half of a rectangle of linen, then the spare half at the top turned to cover the front surface, ie. with the body finally sandwiched between two layers of linen.

2. The image must look as if it were imprinted off a body, not a painted version thereof. Imprinting by contact, which can be modelled with one’s own hands, feet, face etc given a suitable “paint” leaves a distinctive incomplete image, because it only the highest relief that makes contact that can leave an image. Everything else – the lower relief, e.g. eye hollows etc must NOT be shown. In modern parlance we would say the image must resemble a photographic negative (although that term can be and indeed is a source of confusion). So too is the term “lack of directionality”. Both those terms (“negative”and “directionality”) will be will be discussed later in the Technical Appendix.

3. No sides to the body, on assumption that linen does not make good contact witjh sides if draped over loosely, and even if it did there would be a tendency for imaginary “sweat” to drip down under gravity. Similarly, no imaging of the top of the head, which is the same as a vertical “side”. But one is allowed to image the vertical soles of the feet on the dorsal image (see below) if it is assumed that linen had been pulled up and around by burial attendants.

4. .The body image should be a discoloration of linen, maybe difficult to make out, compared with conventional paintings, but not too hard. Make it yellow or pale brown to stand out against white linen.

5. Choose a weave that is receptive to one’s imprinting process. A twill weave (e.g. herringbone 3/1 weave) has more flat areas than a simple 1/1 criss-cross one.

6. Thei mage should have what artists would call form but no outline, to avoid risk of seeming to have been painted.

7.The image should be somewhat fuzzy, not sharp.

8. The image should seem highly superficial, i.e. not have an encrusted appearance that might be mistaken for applied pigment.

9. A body that leaves a sweat imprint would have been unwashed. If the image is to be seen as that of Jesus it must therefore have his blood from open wounds and scourge marks too.

10. It is sufficient to place blood in all the correct biblical locations. There is no need to create images of the broken skin itself, since it is only intact skin that sweats, not open wounds . So the scourge marks too must be imaged as blood, not sweat, which may be problematical but is not insuperable.

11. Hair is somewhat problematical. One cannot make the hair seem as if painted. One has to imagine how an imprint of sweat-sodden hair might look as if imprinted onto linen. It must have the same character as the skin imprint, and only be recognizable as “hair” by its overall shape and location.

12. The eyes must be closed. It is an image of a recently deceased man.

13. Feet are a problem. Does one terminate the dorsal imprint at the heel, as would be expected, thereby leaving an image lacking feet? Or does one image-imprint off a template as if the linen had been pulled up around the heels and pulled tight against the soles to capture those surfaces as well (creating an option for adding blood imprints too on soles of feet issuing from crucifixion nail holes)? Go for that latter option, since human intervention with enveloping a shroud around the feet is not inconsistent with the the 1st century rock tomb scenario and indeed serves to enhance it.

14. The chin and neck are also problematical. Cloth laid loosely over the frontal surface would tend to bridge from chin to chest, creating a detached floating head with no neck. But cloth that imaged the neck, as if it had followed all the contours would risk imaging the underside of the chin too, making the neck look too long. Some compromise is needed, to get some neck and not too much underside of chin. Maybe simulate a crease at the chin to suggest there had been pressure applied to the linen, manual, or maybe from having a ‘neck tie’ of some kind that would not itself be imaged.

15. Loin cloth? Problematical. How can it be imaged realistically if all it leaves is a sweat imprint, more or less imprinted? How could it be recognized as a cloth imprint as distinct from uncovered skin. Conclusion: there is no avoiding bare buttocks. Finer sensibilities must take a back seat. Maybe use scourge marks to partially disguise the private skin.

16. Frontal nudity? Use crossed hands to cover the genital area. Take liberties with human anatomy if ncessary (slightly overlong arms and fingers).

Overview: What we see here is the birth by degrees of an iconic image, one that is not strictly speaking a representation of a real person, but an imagined imprint of a real person from some kind of contact template, in which numerous assumptions and compromises have had to be made. Sure, the final body image with its blood additions looks reasonably realistic at first glance, but look more closely and one can see that it is idealized and, most importantly of all, tweaked to perfection (or as some might say, slight mperfection).

Summary

I have set out a possible scenario that led to the TS being fabricated as a rival attraction to the Veil of Veronica, indeed one that built on the established credentials of the Veronica as perceived by those at the time, and which later over several decades and centuries came to supplant the Veronica as the Church’s new “central icon” (to borrow Neil McGregor’s words re the 14th century Veronica).

Imaging mechanism? This posting has deliberately been kept free of mechanisms by which the “sweat imprint” was or might have been fabricated. That is deliberate. The idea mooted here regarding the aim and motivation for creating the TS image as a simulated sweat imprint should not be based or judges on practical, technological details of executing that objective. The latter have been extensively discussed previously by this blogger in well over 200 postings (a flavour of these has been consigned to my single opening graphic and a technical appendix that will follow in due course) They should be judged purely in terms of human motivation: why would a medieval artisan and his sponsors have wanted to go to all the trouble of creating an artefact that could be passed off as the genuine burial shroud of Jesus Christ? Which details would need have been got exactly “right” to achieve those ends. Which could have been slightly altered in the interests of practicality and artistic licence? The rest as they say is history (and appropriate technology).

I have as yet no clinching evidence, needless to say, and may never do so, but this new perspective, dare one say paradigm (as in “paradigm shift” this blogger having long nurtured an ambition to declare a paradigm shift, especially one of his own making) hopes there are enough anomalies accounted for re the otherwise perplexing TS image for these ideas to receive serious consideration.

Wish to know more? Comments invited, here or or my main sciencebuzz site.

Recent Shroud-related postings on sciencebuzz:

http://colinb-sciencebuzz.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/turin-shroud-negative-image-several.html

http://colinb-sciencebuzz.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/ive-been-misunderstood-i-did-not-claim.html

http://colinb-sciencebuzz.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/checklist-of-reasons-for-thinking-turin.html

Technical appendix and image gallery

Here’s one route to simulating the TS image as a “sweat imprint” (there may well be others), This one is purely thermal (“contact scorch” onto untreated linen, but one could explore thermochemical imaging, onto pretreated linen, or possibly ones that are entirely chemical at room temperature, though less probable). Forget those radiation models – they are pseudo-science unless the precise wavelength range and image focusing/image-reception chemistry are specified).

It’s arguably the so-called lack of directionality in the pattern of light and shade that is the Shroud image’s chief and immediate peculiarity (apart from light/dark reversal). It makes the Shroud image look “flat” despite the cryptic 3D properties that can be shown with digital enhancement software (e.g. ImageJ). Ordinary photographs generally allow one to deduce the location of a light source, assuming one only.

Lack of directionality (and the other peculiarities) is a feature of imprints obtained from a template,i.e. physical contact, and distinguishable in that respect from photographs, including those theorized 1st century or later anachronistic “proto-photographs” that have been proposed, generally without a sound scientific basis.

Modelling the Turin Shroud: heat up a metallic 3D template of one’s desired subject.

Here’s the 3D enhanced version of the same scorch image prior to conversion to a light/dark reversed negative.

Here’s an image needed to make a point elsewhere (on another’s site):

Details from the Machy mould. Left hand image: The face above the word SUAIRE (reversed). Are the eyes open or closed? The face of one of the two clerics supporting the shroud is shown for comparison (right hand side).

.